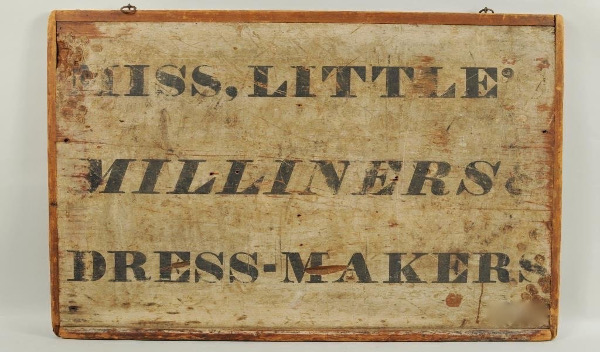

Biography - Alexander Calder

Had Roxbury Connecticut's Alexander "Sandy" Calder (1898-1976) assumed a career as toy-maker instead of the most innovative and popular sculptor in American history he likely would have been a fashioner of kites, yo-yos, balsa-wood planes and something like the Slinky. Except that his whimsical models would be of his own invention. For Calder, like most artists to whom history anoints the title of Master, did much more than skillfully follow in the footprints of his forebears and contemporaries. He blazed new trails.

The Pennsylvania born son of two generations of artists and sculptors graduated with a Master of Engineering degree from Stevens Institute of Technology in 1919 and began working at various jobs including drafter, logger and riverboat firefighter. In1923 he enrolled at the Art Students League in New York City. In the fall of 1926 he moved to Paris and began producing amusing animates from paper, rags, wire and wood. "Le Cirque Calder," a menagerie of circus figures accompanied by Victrola music and the artist as enigmatic ringmaster soon won the hearts of Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp and other members the French Avant-garde, sending Calder's artistic métier into orbit. "Why must art be so serious?" this rugged new American seemed to ask. It was the first of many questions Calder would ask and then answer.

By 1930 Calder began producing his first purely abstract sculptures. He joined three-dimensional shapes with wire so that they seemed to emanate from space. These he put into motion, first mechanically and then by wind and air alone. Marcel Duchamp coined a new name for the artworks, calling them "mobiles." Later Jean Arp would invent a name for Alexander's works that did not move, calling them "stabiles." When Calder's sculptures made their New York City premiere at a gallery in 1932, a New York Times' critic wrote,

"There is something absolutely new in the sculpture at the Julien Levy Galleries …where "Mobiles" by Alexander Calder were placed on view yesterday … "Mobiles" are abstract sculpture set in motion … The bits of wire, now and then with a colored ball, weave strange patterns when a motor is turned on … Amazing you agree, but is it Art? What is art itself? We seem to have here, somehow, more than just an idle diversion."

Although Calder was breaking new grounds in art he had not yet found a way of breaking records in sales - scratching the pad not once at his New York show.

Calder married Louisa Cushing James in 1931. Two years later they traveled to America and began hunting for a residence that would prove inspirational as both home and workshop - a place where the wind would stir Calder's mobiles and the landscape itself would stir the birth of immense stabiles. When the young couple were shown a spacious dilapidated 18th farmhouse on eighteen acres of rolling land in Roxbury, CT they exclaimed, according to their grandson, "That's it."

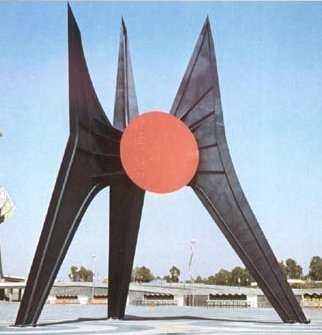

Alexander Calder worked in almost every artistic element including painting (primarily gouache work) and drawings. Later in his career, often working with the Segre Iron Works of Waterbury - builder of many of his works - he would become known for his huge arching abstract sculptures that now find habitat in plazas and parks worldwide. One of the most famous is a huge red "Stegosaurus" stabile located adjacent to Hartford's Wadsworth Athenaeum.

Calder was a tireless worker. Since 1987 the Calder Foundation has documented more than 17,000 of his works for future publication in a catalog raisonne. While the odds of locating a major sculpture is negligible, original Calder art sometimes appears in the form of witty gifts he crafted for his friends and neighbors: Stationary bearing original art, personalized silver and steel jewelry, kitchen utensils spun out of wire, an aluminum bread pan, birds and pull train toys forged from tin cans, andirons, a wood-carved mouse, a flower shaped from pipe cleaners or a dinner bell made by hanging a wire-suspended cork upside down inside a glass bottle.

His friends have described Calder as a curious, quiet, likeable man whose hands and thoughts were always in motion. He was serious about matters of the world and totally devoid of pretensions. His art can be viewed in numerous books and at many museums including the Whitney Museum of Art (NYC) and Hartford's Wadsworth Athenaeum. In addition to having a flair for new approaches to art, Calder had a flair for art itself. His work is distinctive. After spending a little time the man you'll discover that artist's hand was a fresh and original as his imagination.

Norman Rockwell - Biography

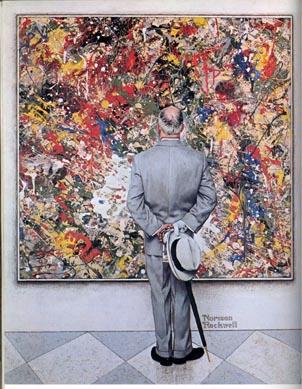

Norman Rockwell's January 1962 Post cover was atypical of what America had become accustomed to since he landed his first commission with the magazine in 1916. It wasn't comical. In his realistic almost photographic style Rockwell depicted of the backside of businessman standing in a gallery, contemplating the meaning of a huge abstract painting that looked as if the artist had dripped his multitude of oils from a stick or can onto the canvas while it was lying on the floor. The illustrator's rendering of Abstract & Concrete must have been indicative of what Rockwell, then 68, was pondering at the time. "How will I be remembered? As a technician or artist? As a humorist or a visionary?" This was the beginning of one of the most turbulent times in America. When the seriousness of the 20th century would become even more serious. A century in which the majority of those deemed as socially significant art critics would use words like "master" to describe modernists like Jackson Pollack while scoffing at the artisan most popular to the people.

Employing themes of patriotism, diligence, family, courtship, holidays and small embarrassments we can all relate-to Norman Rockwell celebrated ordinary Americans at play and at work with remarkable warmth and humor. In the sixties his subjects broadened to include political portraits, poverty, race relations and the space exploration. "Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed ," he said. "My fundamental purpose is to interpret the typical American. I guess I am a story teller."

At age 16, having already earned a commission for four Christmas card paintings, Rockwell transferred from high school to study at the Chase School of Art, the National Academy of Design and then at the Art Students League. He sold his first of 321 cover paintings to The Saturday Evening Post at age 22.

An indefatigable worker, the 140 lb. almost 6' illustrator produced over 2000 original works in his lifetime that can be collected now as they appeared in ads, merchandising, books, posters and magazines. Most of his originals have been destroyed by fire or are housed in permanent collections. Rare early unmarred magazines and other collectibles with Rockwell illustrations can command hundreds of dollars today. In addition to The Saturday Evening Post his clients included: Edison Mazda Lamp Works, Encyclopedia Britannica, Fisk Tire, Interwoven Socks, Maxwell House Coffee, Overland Cars, Parker Pens, Coca Cola, Brown & Bigelow, the Boy Scouts, Ford, Hallmark, Mark Twain Book illustrations for Heritage Press, American Magazine, Boy's Life, Judge, Good Housekeeping, Look, McCall's, St Nicholas Magazine, Woman's Home Companion, Literary Digest, Motion Picture Companies, and the US Government-especially for war posters. Instead of painting now and selling later, an illustrator produces work on commission. The thing to keep in mind when investing in Rockwell antiques is to look for items he worked on to assist his sponsors' businesses. Generally I advise you to stay clear of Rockwell collectibles issued, mostly post-1970, as commemoratives. Consider Q and R in the Antique Talk's ABC's of collecting: Question that which looks antique but not old. Regard that which looks old but not antique.

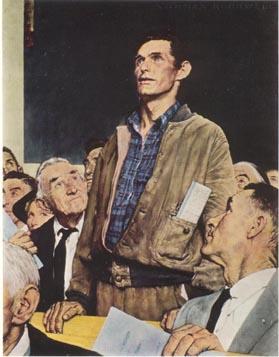

During WWI, the Navy refused young Norman's enlistment request for being 8 pounds underweight. After a night of gorging himself on bananas, liquids and donuts he was mustered in. To his chagrin, he would be employed as a military artist, not a fighter. During the century's second world war, Rockwell learned that he could play a more important role with a pen than most can by sword. In 1943, after toiling night and day at his easel for seven months and losing 15 pounds, Post published his monumental Four Freedoms series. The inspirational paintings were based on postwar principles for universal rights as declared by President Roosevelt in a January 6, 1941 message to Congress: 1. Freedom of Speech 2.Freedom of Worship 3. Freedom from Want 4. Freedom from Fear

Public reaction to the Four Freedoms was overwhelming. Rockwell's paintings touched internal chords important to free people everywhere. The government reproduced the works as posters that reinvigorated populace aid in the war effort. The Treasury Department toured the four originals to sixteen cities. Almost a million and a quarter war-strapped people appreciated them in person. The $130,000,000+ of bonds raised subsequent to the Four Freedoms was instrumental in shortening WWII.

In 1973 Norman Rockwell helped to establish a custodianship of his 574 of his original paintings and drawings near his home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. It is open daily, May-October. In 1977 he received America's highest Civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom for "vivid and affectionate portraits of our country." He passed away peacefully in 1978, at age 84.

In his oil painting, Triple Self-Portrait, for a February 1960 Post Cover, Norman Rockwell pictured himself at an easel. For inspiration, clips of four small self-portraits were pinned to the upper right corner of his canvas: Durer, Michelangelo, Picasso and Van Gogh. A hundred years from now another painter will likely tack portrait prints of his or her heroes for inspiration. Perhaps those masters will include a boyish, lanky, hard-working illustrator: someone known for his enormous Adams apple and even larger heart. More than any other artist, and arguably more than any other storyteller, he recorded 20th century America.

Biography - Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795) is the most influential figure in the history of Western civilization ceramics. When his father Thomas, a relatively unsuccessful potter, died in 1739, the nine year old boy from Staffordshire, England was put to learn the "art, mistery and imployment of throwing and turning" in the family business. Forthwith, he developed exceptional skills. Three years later, he developed virulent case of smallpox that ruined his right leg and forever curtailed his ability to perform physical work. As he would all his life, the boy adapted. Inventive and market-oriented he turned his attention to reading, researching and experimenting "to try for some solid improvements as well as in the Body as the Glazes, the Colours, and the Forms of article of our manufacture." In 1749, in what had to be one of the worst personnel decisions of all time, his older brother refused Josiah partnership in the family business. No doubt, Josiah's imagination and spirit for experimentation intimidated Thomas Junior.

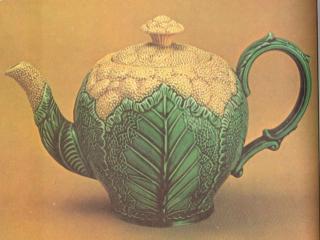

In 1754 Wedgwood (notice there is no "e") entered into a five-year partnership with the 2nd most innovative ceramicist of his day, Thomas Whieldon, forming the Lennon /McCartney of pottery methodology. Together, they developed an ivory colored silken type of low-fired earthenware called "creamware." They also introduced improved vibrant green and other beautifully colored glazes including mottled "tortoiseshell" ware. Adapted to mid-18th century rococo taste, the partner's "pineapple" ware was shaped organically: Form, texture and coloring parroted cauliflower, melons, cabbage, and of course pineapple. Rare surviving teapots and other sophisticated examples of these wares command thousands of dollars each today.

Around 1766, Wedgwood took onto partnership with his cousin, Thomas Wedgwood and businessman and friend, Thomas Bentley. They hired artists and engineers and introduced revolutionary mass production techniques to their factory. When public interest was drawn to excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum and taste turned to Classicism (1750-1800), Josiah adapted. He improved the quality of his creamware and molded it in urn-like vases and Corinthian column shaped candlesticks and other classic forms. The product achieved worldwide success and met with such favor to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, she allowed her name to be affixed to it; "Queen's ware."

In 1774 Wedgwood introduced the line he is most identified with today. Jasper ware is white, granularly textured, thin-walled stoneware stained shades of blue (the most common), sage green, olive, yellow, black, and pink. The singular shades provide background for white bas relief work in classical design.

Wedgwood pottery is still being made today. Almost every piece is identified by factory marks and beginning in 1860 registry marks, that can help in determining age. For example, "England" was added to the Wedgwood mark in 1891 to conform to the McKinley Tariff Act. Earlier pieces are generally superior in quality. Wedgwood pottery is probably the most imitated in history.

Wedgwood is a name we use to denote blue and white jasper ware. Josiah, the man, was more than that. In addition to being a great innovator, scientist and businessperson; he was a good man. He supported the American cause in the Revolution and had ceramic portraits made of Washington and Franklin. He was also a supporter of the 18th century Anti-Slavery Committee and ordained a cameo medallion depicting a slave kneeling in chains surrounded by the inscription, "Am I not a man and a brother?" Benjamin Franklin said of Wedgwood's tokens, "they may have an effect equal to that of the best written pamphlet." Although thousands were given away free to anyone who shared Josiah's sentiments on slavery, I have never seen one in person. It's something to keep your eyes open for next time you're antique hunting.

Biography - Frederic Remington - Part I

James Chillman, former Director of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, said of Frederic Remington, "Some people tell stories so well that their method of telling becomes identified with themselves."

"I paint for boys," Remington said, "boys from ten to seventy. I knew the wild riders and the vacant lands were about to vanish forever...and the more I considered the subject, the bigger the forever loomed. Without knowing how to do it, I began to record some facts around me, and the more I looked the more the panorama unfolded."

July, 1907, President Roosevelt said of Remington, "He is of course, one of the most typical artists we have ever had, and he has portrayed a most characteristic and yet vanished type of American life. The soldier, the cowboy and rancher, the Indian, the horses and the cattle of the plains, will live in his pictures and bronzes, I verily believe, for all time."

Frederic Sackrider Remington was born in Canton, NY, October 1861, the son of a newspaper owner who established the successful St. Lawrence Plaindealer in 1856. Two months following his son's birth, Seth Pierre Remington would leave his family and business to help establish Swain's Cavalry, a regiment that won fame as the Fighting 11th New York . After four years of skirmishing in western campaigns, Seth returned home a distinguished lieutenant colonel and resumed his business.

An indifferent student, Frederic's boyhood enthusiasm centered on caring for the local fire-wagon horse team, swimming, boxing, football, and his sketch-book of horses, soldiers, cowboys, wild Indians, and imagined battles. A Yale Art professor described him as "a queer looking student, frequently having his face and legs bandaged."

Eighteen-eighty was a cruel year. Remington lost his father, left school, failed at several clerical jobs, and fell in love with a young woman named Eva Caten. Unfortunately, Eva's father denied the courtship because of Frederic's uncertain financial position. Broken, the young man fled Westward, to free his spirit and make the fortune needed to win his love.

In his twenties, Remington worked as a cowboy, rancher, gold panner, saloon keeper, store merchant, and as an Indian mediator-all the time, sketching and painting. The artist had discovered his medium and journal's like Harper's Weekly quickly discovered him. He returned to New York and married Eva.

Remington worked with in oil, water color, wash, and pen-and ink. Many of his artworks were based on saddles, boots, uniforms, Indian gear, weapons, and other objects he collected in his western travels-recreating cowboys in his New York studio. In 1890, he illustrated Longfellow's epic limited-edition poem, The Song of Hiawatha. In 1893, ninety-six of his pictures sold at an American Art Association Show for the amazing sum of $7,008. October 1, 1895, his first sculpture, Bronco Buster, was copyrighted. Three weeks later Harper's Weekly devoted a full page to the two foot tall bronze model masterpiece. Remington rejoiced in his new success. "I have always had a feeling for mud," he said.

Remington's one monumental bronze, The Cowboy, was unveiled in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, June 20, 1908.

Remington and Eva achieved fame and wealth in their lifetime. In 1908, at age 48, Frederic was made an Associate Member of the National Academy of Design. Sadly, he died a year later of appendicitis.

During the last 20 years of his life, Frederic Remington worked at a frantic pace. He authored several books and scores of magazine articles. He served as a war correspondent. He modeled 24 bronze sculptures and over 2,700 pictures that are still being copied today.

We will talk collecting and seeing authentic Remington art next week. Until then, happy trails.

Biography - Frederic Remington - Part II

The bronze did not sell. It happens frequently in the auction business. Bidding fails to reach a minimum selling level as agreed by on by both the auctioneer and the consignor. Steven Liebson, of Three Generations Antiques, was working with his family business, Astor Galleries in those years. He was looking at the valuable Frederic Remington sculpture called, The Rattlesnake, when the phone rang.

"Steve, this Ira, from Spanierman Gallery. I've got an important client interested in the Remington. He wants to look at it alone … after hours, OK?"

"Sure," Steve said.

Five-thirty PM, a long black limousine pulled up to the curb. Two tall men, hopped out, nodded hello, and began casing the building, wall to wall. After a few minutes, one of the men returned to the car to escort his boss inside.

Who was this customer? Steve thought, a movie star, a gangster, maybe a Texas oil baron.

As described in writings from the Frederick Remington Art Museum (315-393-2425) in Ogdensburg, New York, Frederic Remington (1861-1909) cast 22 different subjects in bronze. The first foundry with which he worked was the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company in New York. Four different sculptures were cast, starting in 1895, using the sand-casting method. They were the Broncho Buster, the Wounded Bunkie, the Wicked Pony and the Scalp. In 1900, Remington began working exclusively with the Roman Bronze Works, New York. They produced his bronzes using the lost-wax bronze casting process until his death in 1909.

Remington's widow, Eva, authorized the foundry to continue casting Remington's bronzes, still using the same molds, until her death in 1918. In accordance with Eva Remington's will, the molds were destroyed by the foundry shortly after her death. There is no such thing as an "authentic reproduction" in the case of Remington bronzes. If you are wondering whether something is original or not, consider the price that's being asked and the circumstances under which it is being offered for sale.

Here are three things to look for to reassure yourself further that a particular sculpture is not an original Remington bronze: 1. Foundry mark. Most copies bear no indication of where they were made. Authentic sculptures are made with the foundry's name clearly cast into the bronze base. 2. In very few instances will an authentic cast be mounted on a marble base. Copies are frequently mounted on them.

There is always great curiosity about numbering. Original bronzes are numbered sequentially. They were made and numbered more or less according to the demand, i.e. 1,2,3, etc., not 1/100 or 19/50. Many copies are misleadingly numbered in this second "3/100" fashion. The location of the number on original sculptures is usually under the bronze base." 3. If it's priced less than $100,000.

Genuine "first period" Remington bronzes, paintings, and other artworks are beyond the means of all but the wealthiest collectors. Two areas still obtainable are books and prints.

Remington was one of the highest paid illustrators of his day. By 1890 more than two hundred of his illustrations had appeared in Harper's, Century, Outing, and Collier's Weekly magazines and in numerous books, several of which he authored.

Ben Franklin - Newspaper Columnist - Part II

Gentle Readers, Thank you for granting me a second week in your company as substitute columnist. As the first half of my tale explained, I've had experience in this capacity. With your kind indulgence, I thus conclude my biography. Your humble servant, Ben Franklin.

In 1732 I first publish'd my Almanack, under the name of Richard Saunders; it was continu'd by me about twenty-five years, commonly call'd Poor Richard's Almanac. I consider'd it as a proper vehicle for conveying instruction of temperance, frugality, industry, and humility among the common people, who bought scarcely any other books. I considered my newspaper, also, as another means of communication. In its conduct, I carefully excluded all libelling and personal abuse, which is of late years become so disgraceful to our country.

continu'd by me about twenty-five years, commonly call'd Poor Richard's Almanac. I consider'd it as a proper vehicle for conveying instruction of temperance, frugality, industry, and humility among the common people, who bought scarcely any other books. I considered my newspaper, also, as another means of communication. In its conduct, I carefully excluded all libelling and personal abuse, which is of late years become so disgraceful to our country.

In 1736, I formed America's pioneer company for extinguishing of fires called the Union Fire Company. That same year, I lost one of my sons, a fine boy of four years old, by the small-pox. I long regretted bitterly, and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation.

In 1737, Colonel Spotswood, late governor of Virginia, offered me postmaster-general. I accepted it readily, and found it of great advantage; for, tho' the salary was small, it facilitated the correspondence that improv'd my newspaper. In 1742, I invented an open stove for the better warming of rooms and saving fuel. To promote that demand, I wrote and published a pamphlet, entitled "An Account of the new-invented Pennsylvania Fireplaces."

At mid-century, having helped in the establishment of paved streets, street lamps, a defence militia, Pennsylvania Hospital, and the University of Philadelphia, I flatter'd myself that, by the sufficient tho' moderate fortune I had acquir'd, I had secured leisure during the rest of my life for philosophical studies and amusements. However, the publick, now considering me as a man of leisure, laid hold of me. The governor put me into the commission of soldier and treaty arbitrator in the French-Indian War. The corporation of the city chose me of the common council, and soon after an alderman. The citizens chose me to represent them in Assembly.

On October 19, my first accounts of the "Electrical Kite" and "How to Secure Houses, etc, from Lightning by means of pointed rods" appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette.

I was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and there said, "We must all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hand separately."

And now to conclude, experience keeps a dear school, but fools will learn in no other. I leave you with a few of maxims from Poor Richard:

Innocence is its own defence.

Wealth is not his that has it, but his that enjoys it.

Hunger never saw bad bread. He that drink fast pays slow.

Do good to thy friend to keep him, to thy enemy to gain him.

An old young man will be a young old man.

Now I have a sheep and cow, everybody bids me good morrow.

Fish and visitors smell in three days.

A country-man between two lawyers is like a fish between two cats.

The worst wheel of the cart makes the most noise.

Time is the herb that cures all diseases.

Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy wealthy and wise.

Keep thy shop and it will keep thee.

God helps them that help themselves.

Little strokes fell great oaks.

Three may keep a secret if two of them are dead.

An egg today is better than a hen tomorrow.

In the affairs of this world, men are not saved by faith but by the want of it.

Adieu.

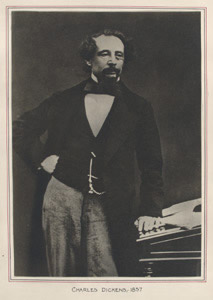

Dickens' A Christmas Carol

John Dickens, a Naval Pay office clerk, saw to it that his eight children received schooling. He aided their education by returning home from work with cheap reprints of 18th century novels like Robinson Crusoe, Tom Jones, and Peregrine Pickle, that delighted his family. His London colleagues described him as "a well-dressed fellow of infinite humor; very courteous, imposingly so; the jolliest of men." John's flaw was a poor head for finance. The eternal optimist described himself as "a cork which, when submerged, bobs up to the surface again, none the worse for the dip."